Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B Construction Photos

Page 34

VAB in the Distance, 112' Level Hypergol Area, Flame Deflector

(Original Scan)

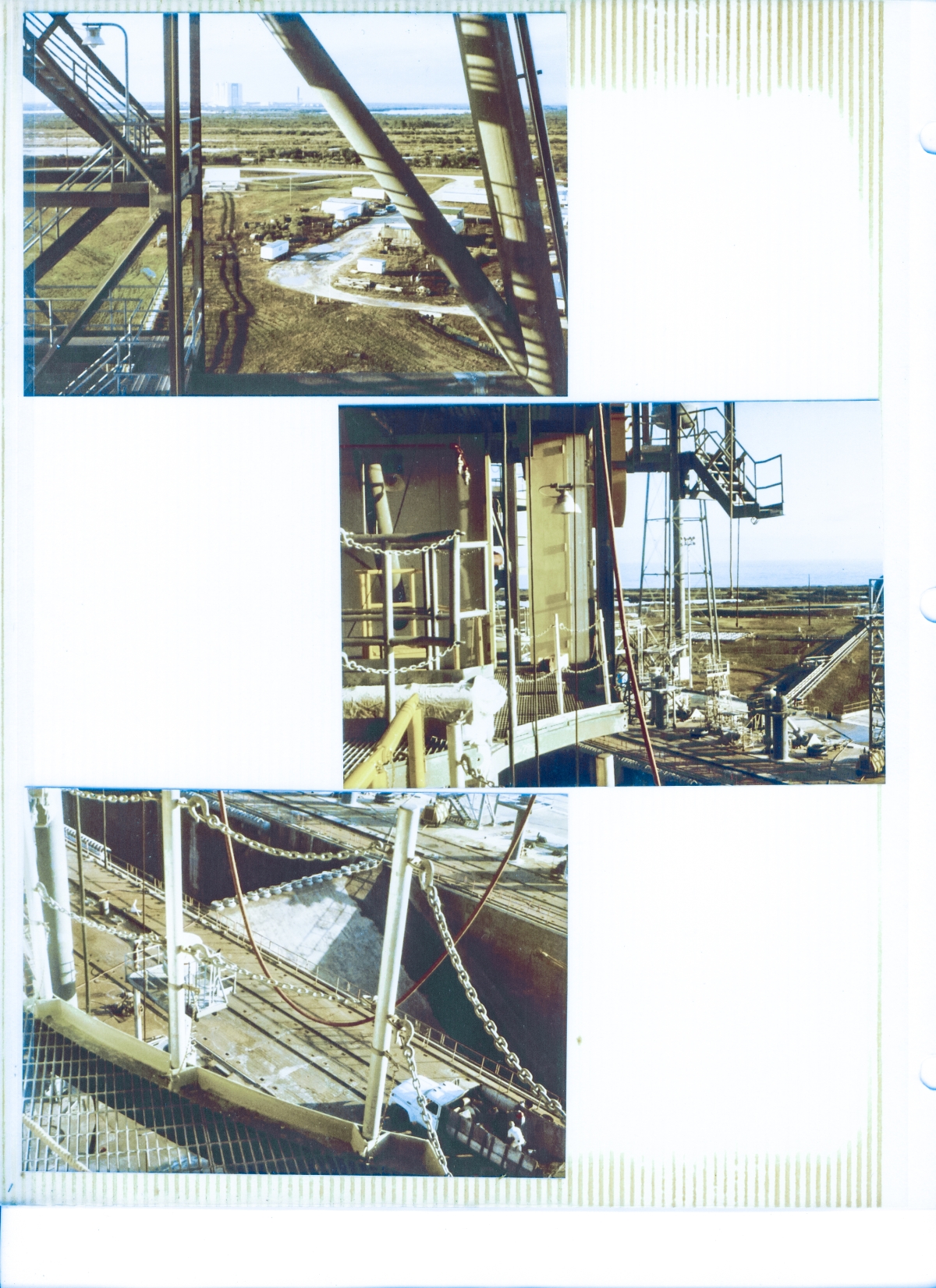

Top: VAB and last LUT with Milk Stool, seen through the Stair Tower and Primary Structural Framing of the RSS.

Center: More Stairs of Doom.

Bottom: Flame Trench and Flame Deflector. The Flame Deflector, by the way, was coated in a sort of refractory gunite called Fondu Fyre. What a perfectly wonderful name! I've always loved it just because it sounds so weird.

Also, down under that Flame Deflector is a whole weird and wonderful dark world. The interior of the pad is not solid all the way through. There are catacombs down there, complete with growing stalactites up in dim corners, the occasional inadvertently-cornered raccoon, or who knows what else, spooky, echoey, creepy dim halls and mystery rooms, and in the middle of it all, around a perfectly nondescript corner, there's a little door, that you can stoop through, and come out up inside of the steel structure of the Flame Deflector. I always loved spelunking in the catacombs, and did so at every opportunity.

Additional commentary below the image.

Top: (Reduced)

Just another one of those views.

The hulking mass of the VAB was always there whether visible in the distance, or not.

It is itself, and it is also, at the very same time, something other.

We read what we will, into that which we see, and there are certain things that bring this aspect out in people to a larger degree than usual, and the VAB is one of those things.

I am not one to believe in spirits, afterlives, gods, or devils, and yet...

The air seemed to hold something in the vicinity of that colossal box, squatting enigmatically on the horizon, ever-present, ever-mysterious.

And that, even though I knew full-well exactly how it was constructed, and exactly what it contained, and exactly what went on in there daily, and had visited it more than enough times to develop a workman's familiarity with it, and was under no illusions that anything special might have been going on with it.

And yet...

The shadows cast by Apollo were very long, and they were also, in a certain peculiar way, very dark.

The gods themselves would have been awestruck with the work that came, was, and went, in and around that box.

The builders of Stonehenge or perhaps the Pyramids would have understood exactly, that telling strike of awe.

And so it is early morning, and you find yourself down on the very lowest level of the RSS with some free time to loiter, to consider, to perhaps let the air fill your sails and propel you, if only for a few moments.

And the VAB sits there, beyond the heavy iron and stair tower of Column Line 7, Sphinx-like, inaudibly speaking to you.

And one day the sea will rise and take it, take the very ground it rests upon, and it will be gone, and the shadows will only get darker.

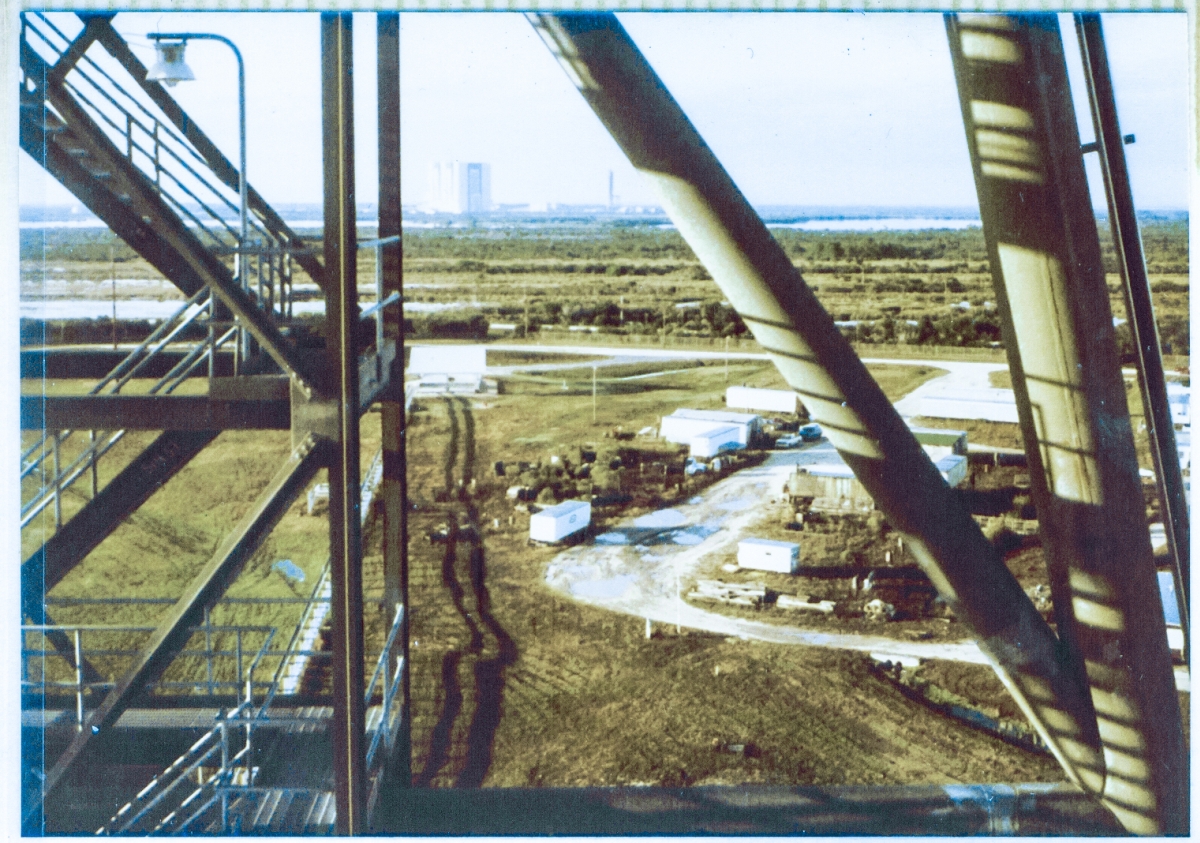

Center:

(Reduced)

And here we find ourselves down on the 112' level of the RSS, in the vicinity of the Hypergol Umbilical Carriers (which had yet to be fabricated and installed), near the cutout in the floor framing that accommodated the orbiter's tail.

Across the way, on the left side of the frame (if you look close, through the intervening welter of handrail pipes) a diagonal structural pipe can be seen coming up, toward and a bit to the left of where you're standing, and beyond its bottom end, where it disappears, lies the bland nothingness of the exterior of one of the ARCS Rooms (there was a pair of them, one on either side of the orbiter).

The Hypergol Umbilical Carriers and the ARCS Room were both associated with handling the hypergolic propellants that the orbiter's OMS motors, as well as the aft reaction control system's motors, used to do their jobs.

Near-center, coming down from out of the top edge of the frame and gently-curved near its bottom margin, just to the right of the white shade of one of the pad lighting fixtures and partially obscured by the dark vertical extent of a steel column and some dull-orange hose, can be seen one of the Hypergol Spill Ducts, which was also associated with the handling of that fuel and oxidizer, and which you sincerely hoped would never ever be needed, at all, or at least not while you were on the pad.

This frame is early on in things, and the hypergol systems were a long ways from going live, so there was no threat from that quarter at this time.

Later on, while we were still out there working, the system DID go live, and I distinctly recall having been appointed by my boss to gather all of our ironworkers together one morning prior to going up on the towers and going to work, and giving them a specialized one-time safety lecture advising them that the goddamned thing was now LIVE, and some of the stainless-steel tubing and piping that was now fully-charged with horrifying poisonous stuff had pretty thin walls, so pretty please guys, try and be a little more careful with things from now on, especially with preventing arc-strikes caused by inadvertently dropping a live welding lead on to any of the nearby thin-wall piping, or otherwise just generally being very careful not to damage anything else in that live system, 'cause you just might kill us all if you do so.

A bit to the right of the hypergol spill duct, in front of the farther-distant SSW water tower, is a hinged-stair which could be flipped up, out of the way, that I do not recall the purpose of, or exactly what it was placed there to give access to.

Notice the complete lack of safety apparatus on this stair.

Sitting there in your comfortable chair reading these words, you might find it hard to imagine how anyone could be so stupid as to walk, or even simply stumble off of the end of something like this, but up on the tower, in the heat of work, things took on a completely different, and much more hazardous, aspect, that mere armchair observers can never share in, understand, or otherwise relate to, intelligently.

It's different up there, that's all.

Just ask anybody who's been there.

In the far distance, below the hinged-stair-of-doom, the placid waters of the Atlantic Ocean give no hint of the look they can take on every once in a while in the months of August, September, and October.

The place can really fool you, and has no end of creative ways to do so.

Below and to the right of the hypergol spill duct, the pad deck, which in no way indicates that it's fifty feet in elevation above the green grass beyond it, bristles with an array of equipment, including SSW headers, MLP Mount Pedestals, and all manner of access platforms and stair towers.

Angling up and away across the grass, to the right of all of that, the cross-country cryo line that took liquid hydrogen to and from the very large dewar it was stored in near the pad perimeter, can be seen, as well as just the smallest dark bit of the curved ball of the dewar itself, mostly obscured by one of the MLP access stair towers, on the extreme right-hand side of the frame, near center, top-to-bottom.

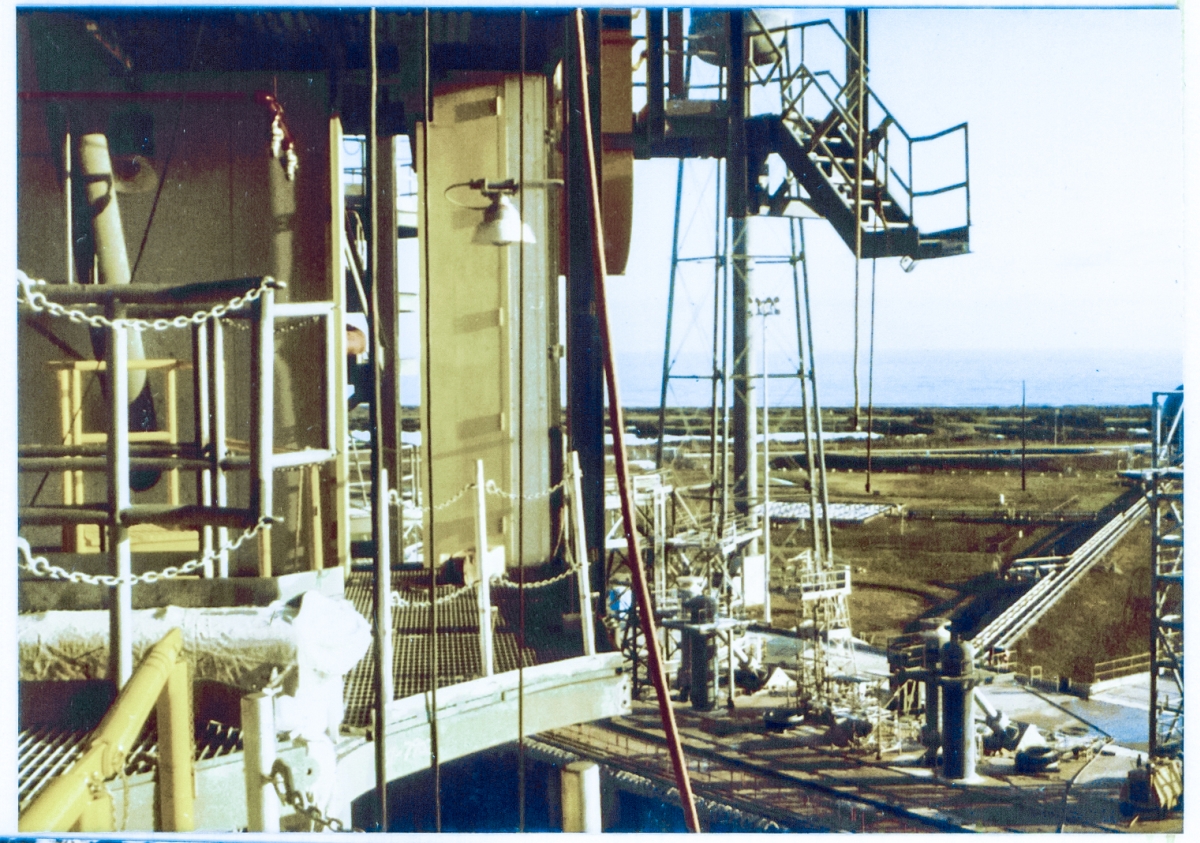

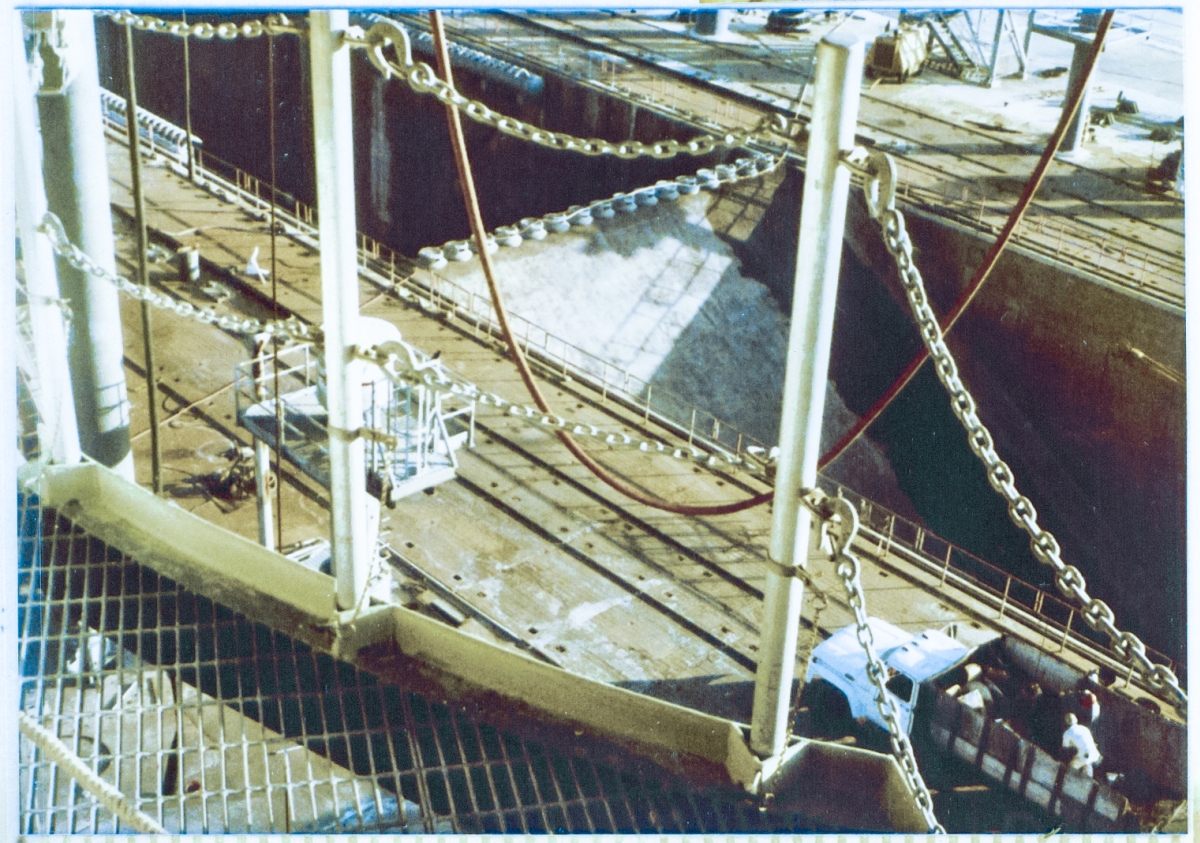

Bottom:

(Reduced)

The Flame Deflector.

You're looking directly at it, right there in the center of the frame, filling up all the space between the five-story vertical walls that make up the flame trench.

When the Shuttle flew, this thing took it right on the chin, and its job was to deflect the impossibly-powerful exhaust to the side, safely away from the Space Shuttle, in order to allow it to get up and away from the pad without destroying itself in the attempt.

Rockets are insanely energetic things, and the larger the rocket, the more insane the energy level, and by the time you've reached the scale of something as large as the Space Shuttle, the human mind loses all hope of properly understanding things directly.

So instead, you start looking around at some of the stuff that's involved indirectly, and you attempt to gain understanding that way.

And you look at the flame deflector, and you look at how big it is and how heavy and close-spaced the iron is that it's made of is, and you look at what it's coated in (and if you're lucky, you will have had an opportunity to look at other, similarly-coated objects that have endured their share of launches and have seen with your own eyes exactly what those launches did to them), and although you are aware that you will still never understand exactly what's going on directly, you begin to get the faintest glimmerings that something perfectly horrific is occurring. Something that you want no parts of. Something to be stayed very far away from when it happens.

As an aside, I'm pretty sure that the fact of having grown up more or less in the shadow of these launch pads is the root cause of my complete lack of interest in fast cars, fast boats, and most (but not all) fast airplanes. Somebody or other is trying to persuade me that the race-car they're talking about is really something, and inside, I'm thinking F-1's and SSME's, and I just cannot bring myself to feel very much at all by way of impressment with something that generates a total output of perhaps a thousand horsepower when compared to things that have fuel pumps that generate 70,000 horsepower. I recall being this way as a small child (this kind of extreme high-energy stuff has fascinated me from day one, and I remain just as fascinated with it now as I ever did), and the feeling has never left me, all my life.

As the SSME turbines ramped up toward full power for six-odd seconds prior to the SRB's kicking in, when the Shuttle starts moving, the exhaust from them sprayed down hellishly, directly upon this thing. Along its top edge, running from one side of the flame trench to the other, a row of closely-spaced spray headers can be seen. The job of these spray headers was to both protect themselves as well as the rest of the adjacent pad, and, most importantly, the Space Shuttle itself.

Just prior to engine ignition, SSW water was pumped furiously through these, and other, spray headers, and in so doing, diluted, not much, but just enough, the ferocious effects of heat, blast, and shock wave, that the Space Shuttle produced when it took off.

Those SSME's were a thing to be reckoned with.

And the SRB's were much worse.

In the immediate near-foreground, you're getting a good look at the removable handrails along the Orbiter mold-line, and can see pretty well just exactly what kinds of components they were made of. A36 steel socket, aluminum post, stainless-steel threaded pad eyes, and galvanized hooks and safety chain. It was a horseshit design, implemented by horseshit people, and I can never look at these kinds of removable handrails without thinking about the level of bullshit we had to put up with, taken to absurd fantasyland levels of disconnect from the real world, enforced upon us by a couple of extraordinarily small-minded individuals, who's mission in life seemed to be one of just fucking with people, and hurting people, for the sheer malicious joy of it. Gah.

Down in the extreme lower-right corner of the frame, a couple of people can be seen in the back of a stake-truck down on the pad deck, and although it looks a lot like Ivey's truck, I cannot be completely sure of that. I recall our truck had our logo haphazardly stenciled in spray-paint on the doors, and I cannot see a logo in this image.

But if it's Ivey's truck, then the gentleman dressed in white coveralls, working with another gentleman on the debris and rubbish back there, would be Robert. I cannot recall Robert's last name, although I wish I could. Robert was a good man, and endured much.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEMaybe try to email me? |